Self-Mastery Nº23

Cognitive bias: the powerful influencer of our mind

Welcome to Self-Mastery — a place of timeless ideas to help you become the architect of your mind and create yourself, starting from the inside.

“Knowledge can be communicated, but not wisdom. One can find it, live it, do wonders through it, but one cannot communicate and teach it.”

— Hermann Hesse, Siddhartha

It’s late. You're wandering home tonight, alone. And suddenly, you hear an unfamiliar sound behind. You feel the sound is a sign of imminent danger. As a result, your pace quickens to get home as soon as possible. On the contrary, you believe it to be nonthreatening, so you quickly calm down from the strong spike in adrenaline. Perhaps, the noise originated from something that means no harm, like a stray cat rummaging through a nearby bin. However, it comes down to the mental shortcut you took to quickly decide whether it was threatening or not. It decides whether you stay out of danger, or stand right in front of it. This way of being is our reliance on cognitive biases, which help us navigate through life and adapt to it.

Cognitive biases are a bit of a tangled mess. Quite simply, it's a systematic (nonrandom, only predictable) deviation from rationality in decision-making. We use these biases to save us both time and energy. But while they help us to make faster assumptions, they are the primary cause of many of our mistakes.

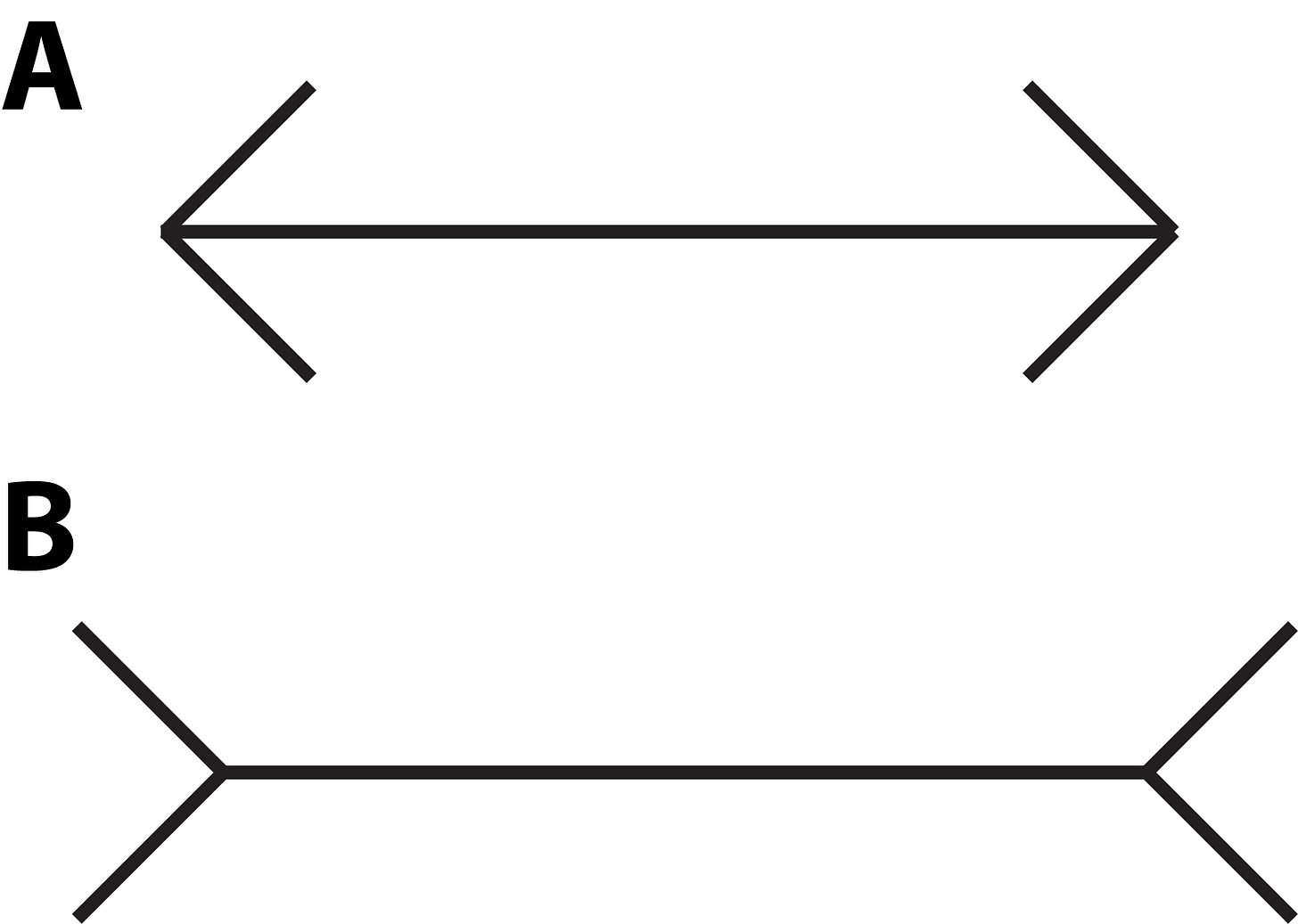

For example, have a look at the picture below. You might recognise this image. So the question is: between a and b, which do you believe is longer?

According to research, Western societies lean into answer b as the answer. In fact, both segments are exactly the same length, they only differ in orientation.

Of course, you could argue that b is, in its current form, longer. But the arrows purposely create an illusion for you to feel as though they differ in length.

This test is to prove how such a simple illusion demonstrates how we can be tricked by very irrelevant information, leading to mistakes in what we think we see. This bias not only affects our perception, but our judgment, our decision-making ability, our memory, etc.

Cognitive biases hide the beliefs and behaviours in us that are dangerous or problematic. Think superstitions, pseudoscience, prejudice, poor consumer choices, among others. And in a group-level, they can create tremendous collective decisions that could cause major crisises among society.

There are four main problems with cognitive biases you should know. They are down below.

Problem 1: too much information.

While we’re blessed with information at our fingertips like never before, much of it is unecessary or negative. Our minds cannot take it all in, and thus we have no choice but to filter almost all of it out. But our brain uses a few simple tricks to consume the most relevant bits of information that will most likely be useful in some way. Some things to note:

We're more more likely to notice things that are related to what's recently in our memory.

Bizarre/funny/visually-striking/anthropomorphic things stick out far more than bland/unfunny things. We boost the importance of things that are unusual and surprising, skipping over what's ordinary or expected—something that news publishers focus deeply on.

We’re drawn to details that confirm our own beliefs. And this is one of the detrimental problems we face as free-thinking individuals.

We notice flaws more easily in others than in ourselves. Many people fail to see it. But cognitive biases are not simply list of problems in the minds of others. It also includes you.

Problem 2: not enough meaning.

The world and society rarely makes sense. But we need things need to make sense in order to survive. Once the reduced the stream of information comes in, we connect the dots, fill the gaps between what we already think we know, and update our mental models of the world.

We find stories and patterns even in sparse data. We never see the full extent of the world and information, so we never have the luxury of the full story. Our minds, then, construct an interpretation of the world to make it feel complete, often mistaking or adding information that isn’t true.

We fill in characteristics from stereotypes, generalities, and prior histories, whenever there are new, specific instances or gaps in information. When we have partial information about a specific thing that belongs to a group of things we're familiar with, our mind will fill the gaps with "best guesses", or what other "trusted sources" provide. We then forget which parts were real and which were filled in.

We imagine things and people we're familiar with or fond of as better than the people or things we aren't familiar with or fond of. This is why someone might buy into everything a celebrity sells, but ignore the work of their own friends.

We think we know what others are thinking. We sometimes then assume that they know what we know (a problem I face as a writer). While in other cases we assume that they're thinking about us as much as we're thinking about ourselves.

We project our current mindset and assumptions onto the past and future. We're terrible at imagining how quickly or slowly things will happen or change over time, so we try to keep how we think the same, when actually, it needs to change.

Problem 3: we need to act fast

Without the ability to act fast, we would’ve perished as a species long ago. With every new piece of information, we need to do our best to assess it, understand it, apply it, simulate the future to predict what might happen next, and act on this new insight.

In order to act, we must be confident in our ability to make an impact and feel like what we do is important. Most instances of confidence can be classified as overconfidence, but without it, we might never act at all.

In order to stay focused, we favour the most immediate, relatable thing in front of us than the delayed and distant. This is why we value the hear and now and relate more to stories of specific individuals than anonymous individuals or groups.

In order to get anything done, we're motivated to complete things that we've already invested time and energy in. This is important! The behavioural economist's version of Newton’s first law of motion: an object in motion stays in motion. This helps us get to the finish, and it's why we attain true motivation after we've started, not beforehand.

In order to avoid mistakes, we're motivated to preserve our autonomy and preexisting beliefs and status in a group, to avoid irreversible decisions. If we must choose, we choose the option that's perceived as less risky or that preserves the status quo. “Better the devil you know than the devil you do not”.

We favour simple and complete options than the complex and ambiguous ones. Generally, people don’t complain about things being too simple; rather, simplicity itself is one of the most sought after components to success in both business (Apple, the greatest example) and relationships (as we're fond of people we relate to, who help us understand things easily).

Problem 4: what should we remember?

We need to make constant bets and trade-offs over what we remember and what we forget. For example, we prefer generalisations over specifics, as that takes up less space. With information we consume, we pick out standout features to save and then discard the rest; what we save is what will most likely inform out mind and fill the gaps. But it's all self-reinforcing, so ample care is essential.

We edit and reinforce memories after the fact. We strengthen our memories over time. But sometimes, various details can be accidentally swapped, and we inject a detail that didn't exist or wasn't true.

We discard specifics to form generalities. This is out of necessity and time constraint, but the impact of this creates some of the worst consequences.

We reduce events and lists to their key elements. It's often difficult to reduce events and lists to generalities, so we instead pick out a few items to represent the whole.

Great. So, how do you remember all this?

It's not necessary, but you can start by remembering our minds have dealt with these four giant problems for millions of years (if you keep hold of this email, you can refer back to it and its resources to help find what you're looking for when you need it).

Information overload is real, and our minds are not capable of having it all at hand. This is why its important to write things down, store information elsewhere, and simplify, but keep things complete and accurate.

To avoid drowning in it all, we now skim and filter with our lower attention spans. And to construct meanings, we fill in gaps and map it to all our existing mental models. All while ensuring it remains stable and accurate.

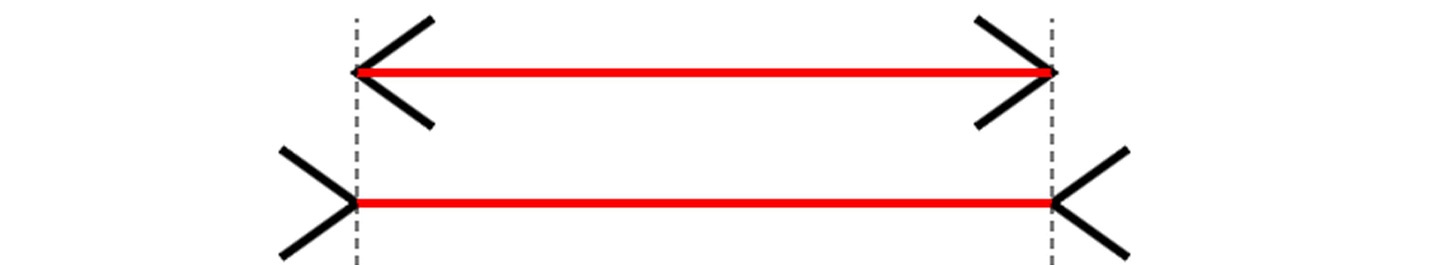

There's nothing we can do to eliminate the four problems of cognitive bias, but if we can accept that we’re permanently biased, and that there's room for improvement, it will help us learn to understand ourselves better and make changes in our decisions to create better results. To show you just how complex it all is, here's an image below to illustrate it:

What’s on My Mind

As now, here in the UK, we’re in lockdown again. It’s given me time for more reflection on this year. So much has happened that I often forget. I easily mistake my tenure as a writer for beyond this year, when this is not the case. I can be grateful for what’s been achieved and the journey’s I’ve begun, but now, I’d say I am quite tired.

Mentally, I feel as though I’m almost completely worn out. There has been so much energy spent over this year that I desparetly could do with a reset before the new year. But the important thing now is to keep doing what I love, which is writing to you, and being grateful for everything that’s happened so far.

Explore

The bulk of this week’s story comes from “Cognitive Bias Cheat Sheet” on Medium. I tried my best to shorten it, but there is still so much great information on it to see, so I highly recommend you take a look.

I’m pretty active on Twitter, so I’m always available there for any questions or help. I also have a host of upcoming articles for you to read over on Medium, so stay tuned for more.

Thank you for reading if you made it all the way down. You being here means the most to me—and right now, it’s what’s keeping me going this far through the year. I really do appreciate it.

Have a stellar week.

—Jelani